by Nathaniel Roy

Cyrus Hamlin was born January 5th, 1811, into a rather large family. His grandfather had seventeen children. He named four after the continents: Africanus, Americus, Asiaticus, and Europus. Next, he had twins named Hannibal and Cyrus. Hannibal was Cyrus Hamlin’s dad, and, when he was born, Cyrus was named after his uncle.[1] His mother was Susan Faulkner who was a daughter of a revolutionary soldier.[2] Cyrus was born in Massachusetts. He had two sisters and one brother, all older. One of his more notable family members was his cousin Hannibal Hamlin. Hannibal, in Mark Scroggins’ terms, was “one of the most influential senators in the country.”[3] Because of this considerable influence, Hannibal joined Lincoln on the presidential ticket and become the vice president.[4] Cyrus Hamlin’s family was no stranger to the spotlight, and Cyrus was no exception to this rule.

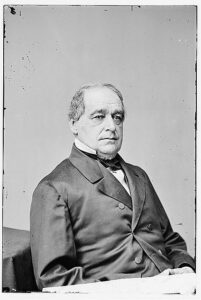

Creator(s): Brady’s National Photographic Portrait Galleries, photographer

Date Created/Published: [between 1860 and 1865]

From the Library of Congress

[1] Cyrus Hamlin, My Life and Times (Boston and Chicago: Congregational Sunday School and Publishing Society, 1893) 9-10.

[2] Hamlin, My Life and Times, 11.

[3] Mark Scroggins, “Vice President Hannibal Hamlin Was Abraham Lincoln’s Most Unused–and Unhappy—Asset,” America’s Civil War 10, no. 1 (March 1997): 12.

[4] Scroggins, “Vice President Hannibal Hamlin Was Abraham Lincoln’s Most Unused–and Unhappy—Asset,” 12.

When Cyrus was first born, he was declared weakly and his head was too big, so his neighbors told his mother that they did not think he would live long. Cyrus’s dad, Hannibal, died when Cyrus was only seven months old. Care for Cyrus from his mother—according to neighbors—is what kept her from her sorrows.[1] After his dad died, his mother was left with two farms and four children. His mother took it upon herself to care for the farmers and look after the children. Some agreed with her decision, but others did not think it was best.

In his autobiography, Cyrus recounts his bad deeds, whether tumbling downstairs or stealing sticks. Cyrus’s family was also deeply religious, and he can remember them reading the Bible daily and strictly following the Sabbath. Altogether, Cyrus depicts a “normal” childhood—he grew up with his siblings and had plenty of stories to tell.

[1] Hamlin, My Life and Times, 13.

Originally, Cyrus wanted to stay on the farm and help his mother, but the family doctor said the manual labor of farming work would likely kill him, so he made the decision to move to Portland, Maine to become a silversmith and jeweler.[1] Cyrus, at first, was rather poor at it, but, along the way, he gained the skills he needed and became a fine apprentice. During his time in Portland he devoted himself to reading religious books. Eventually, Hamlin wanted to start anew for eternal and spiritual good, so he decided to go to college at Bridgton Academy in Bridgton, Maine.

After an eventful time at Bridgton Academy, Hamlin applied to Bowdoin College. He recalled the entry exam as ridiculously hard; nevertheless, he was one of 50 in the freshman class.[2] At Bowdoin, in Brunswick, Maine, Cyrus seriously prepared for missionary work. After graduating from Bowdoin, he applied to Bangor Theological seminary located in Bangor, Maine. He met his wife, Henrietta Jackson, in Bangor, and they married in 1838. The two left the United States that same year and traveled to the Ottoman Empire, where he opened up the Bebek Seminary as part of an outreach for Armenians.

[1] Hamlin, My Life and Times, 47.

[2] Hamlin, My Life and Times, 90.

This seminary was particularly important. This seminary, according to James A. Field’s America and the Mediterranean world, 1776-1882, was founded in 1840 with two pupils.[1] This seminary was founded with an educational mission in the Ottoman Empire, and initially had support from the American Board of Missionaries. After seeing that many urban Armenians had no clothes and were exceedingly poor, Hamlin created skills-based workshops so they could earn wages sufficient to buy clothes and food for themselves and their families.[2]

Hamlin’s skill-based approach was relatively new for missionaries during this period, and most people did not agree with his teachings. The American Board, in particular, did not approve of the bakery, a product of his workshops, from existing.. In Errand to the world: American Protestant thought and foreign missions, William Hutchinson states, “Hamlin thought that when able and earnest people had tried to pursue missionary objectives without teaching English, the results had been equally sad.”[3] Thus, after this disagreement with the Board about education, Hamlin resigned and broke off from the organization. This would then lead him to open a college to educate the Armenians and those who wanted to learn English in the Ottoman Empire.

After the Crimean War and the bread business, Cyrus Hamlin opened up a college in Istanbul and named it Robert College at which he was the president for thirteen years. To raise money for the college, he went back to the United States. This was perhaps one of the darker times for Cyrus because he had virtually no money, but soon, he received a job offer at Bangor Seminary. He remained there three years, and restored his finances.

[1] James A. Field, America and the Mediterranean World (Princeton, N.J., Princeton University Press), 352.

[2] ED: The multi-national Ottoman Empire governed subject populations through semi-autonomous faith groups called millets. Church heads protected religious and cultural rights of millet groups, which had varying degrees of rights and privileges according to Ottoman Law. Until the second phase of the Tanzimat reforms (begun in 1839) members of Armenian millets (Catholic and Orthodox) could not serve in the state bureaucracy or engage in certain professions. See: Masayuki Ueno, “Armenians negotiate the Tanzimat Reforms, International Journal of Middle East Studies, vol. 45.1 (February 2013): 93-109.

[3] William Hutchison, Errand to the world: American Protestant thought and foreign missions (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987), 98.

Subsequently, he went on to be the president of Middlebury College in Vermont, where he opened doors to female students. However, this was not the end of his impact there. After arriving at the school, Hamlin saw that its library was in disrepair and that it gravely needed work. Hamlin proposed a budget to the trustees of the college, which consisted of $7,000 for the repairs, but he was laughed at.[1] He persisted, and proceeded with his plans for the library. According to the Middlebury digital archives, “Many prophesied that he would involve the institution in debt, but all the improvements were made, new books to the value of $1,000 were put into the library and some new apparatus into the laboratories, the gymnasium was fitted up with considerable apparatus and the stipulated sum was exceeded by only $1.50 which the worthy President paid from his own pocket.”[2] These repairs were necessary for the college and prepared it for growth like never before. This job took him to the end of his work life. At this point, Cyrus was 74 years old, and he retired to Portland. Cyrus Hamlin died in Portland on August 8th, 1900 when he was 89.

[1] “Cyrus Hamlin,” Middlebury History Online, accessed May 4, 2021, https://middhistory.middlebury.edu/reverend-cyrus-hamlin-middlebury-college-president/

[2] “Cyrus Hamlin.”