Americans played a significant role in the Crimean War as non-combatants. With the United States government under Franklin Pierce taking a neutral stance, private Americans were free to engage both sides of the war. Some Americans supported the European and Ottoman Allies. Others lined up behind Russia, as memory of the British attack on the United States capitol in 1814 remained all too fresh. Pages in this site examine American activity to better understand the role of non-combatant nations during war. Doing so, we believe, will lead to a deeper understanding of how violence grows around its peripheries.

As our pages show, many Americans traveled to the war zone. Most famously, American military observers visited the camps near Sevastopol in the Delafield Commission. The commission took its name from Chief Army Engineer Richard Delafield and included future Union General, George McClellan. Major Alfred Mordecai, important also for Jewish American history, composed a lengthy exposition of artillery then in use. Around the same time, Samuel Colt went to St. Petersburg to sell weapons. In addition to these better-known figures, American medics, recently graduated from the Sorbonne, volunteered to serve the Tsar’s army. Missionaries spread religion in Ottoman territory and among British forces. War correspondents reported on the front for American journals, while merchants transported and sold goods for both sides.

These men traveled to Crimea and other fronts, often at the height of battle and at great personal risk. Each individual experience contributed to American knowledge acquisition later deployed in American science and industry. More to the point, five years after the Crimean War concluded, the American Civil War began. Both wars heralded a new, industrial stage of warfare featuring mass violence on an unprecedented scale. Americans involved in the Crimean War became crucial conduits of information to the United States, transmitting knowledge from distant battlefields in Europe to the soon-to-emerge home front in the United States.

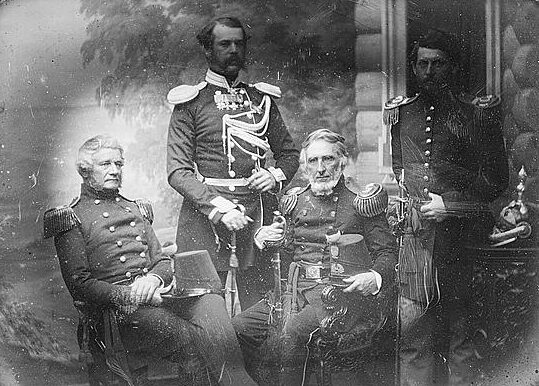

The Delafield Commission

On April 11, 1855, Major Richard Delafield, Alfred Mordecai, and George McClellan set sail for Europe from Boston to research armies and battlefields of Europe. All three men graduated from West Point and had long histories of military service. As head of the commission, Major Richard Delafield had spent a career as an army engineer involved with overseeing the construction of many key American fortifications. With expertise in science and chemistry and a career built around studying artillery, Major Alfred Mordecai’s gathered intelligence on European artillery while traveling with the commission. Finally, George McClellan, then captain of the cavalry, joined the commission as the youngest member with the only combat experience. The intelligence they gathered had a lasting impact on American military forces through the Civil War and beyond.

Americans and the Crimean War: Media

The telegram, railroad, printing press, and the increase in literacy among the average citizens all lead to the birth of a new kind of journalism. The modern war correspondent provided crucial updates on the war from the battlefront that quickly reached citizens back home in only a matter of days.[1] The population could be informed of their government’s handling of the war more than ever before.…

Americans and the Crimean War: Missionaries

A modern conflict of the industrial era, the Crimean War also opened a new stage in world religion. Catholic France and Protestant Britain, two nations historically at odds over intricacies of faith, fought side by side as Allies. These Christian powers joined forces with an Islamic state. Armies of each major combatant, including Russia and the Ottoman Empire, reflected their diverse composition.[1] Karl Marx heralded the Crimean War as the dawn of a new post-religious age.[2]

Of course no such thing had happened…

Americans and the Crimean War: Doctors

Americans and the Crimean War: Merchants

Prior to the war, English, French, and Ottoman ships criss-crossed the Russian Empire’s Black Sea and Baltic coasts in brisk trade. Previously unable to compete in this distant market, American profit-seekers suddenly found opportunity in war. Over the course of the war, American merchants supplied a variety of goods to combatants. Surviving records show, for example, that Samuel Colt sold arms to the Russian Empire, while John Codman helped transport troops for France. Russian agents contracted Benjamin W. Perkins to supply gunpowder to the Russian Empire. Failure of the Tsarist governor to meet the terms of the contract produced an international scandal that dragged on through the sale of Alaska in 1867.