In 1855 at the height of the Crimean War, three American military officials visited the Russian Empire and toured the battlefields of Crimea. The war known for Crimea began in the fall of 1853 as a conflict between the Russian and Ottoman Empires over borderlands in present-day Moldova and Romania. By the spring of 1854, France, Britain, and later Piedmont-Sardinia, entered on behalf of the Ottoman Empire. To break the stalemate that had settled on the western shores of the Black Sea, French and British generals decided to bring the war to Crimea, an area that Russia had conquered seventy years prior.[1] For a year, Allied forces laid siege to the peninsula in the most devastating European military conflict of the nineteenth century.[2]

Steam-warships, long range guns, and sea mines volleyed along Russian borders in the Black and Baltic Seas. Rail facilitated the rapid movement of goods, at least for the British, while telegraph and photographs provided rapid communication of military activities to distant home fronts. Justifying his decision to capitulate Sevastopol in August 1855, Russian general in Sevastopol, M. D. Gorchakov wrote the tsar the mass armies and modern weaponry deployed in Crimea had “no precedent in History.”[3]

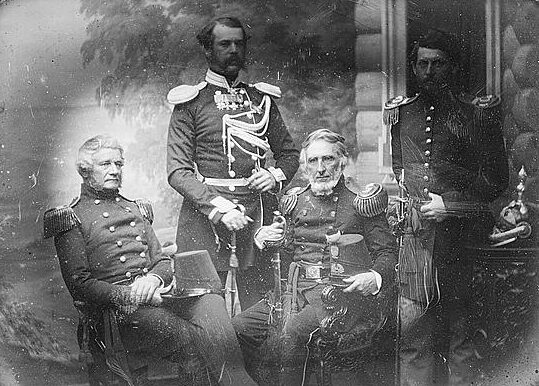

Meanwhile, for the first time in history, Americans became front-row spectators of a war unfolding across the ocean and American military observers came to see Crimea as a crucial laboratory of modern warfare.[4] On April 11, 1855, Major Richard Delafield, Alfred Mordecai, and George McClellan set sail for Europe from Boston, beginning a several month tour of the armies and battlefields of Europe. All three men graduated from West Point and had long histories of military service. As head of the commission, Major Richard Delafield had spent a career as an army engineer involved with overseeing the construction of many key American fortifications. With expertise in science and chemistry and a career built around studying artillery, Major Alfred Mordecai’s gathered intelligence on European artillery while traveling with the commission. Finally, George McClellan, then captain of the cavalry, joined the commission as the youngest member with the only combat experience.[5]

For nearly a year, the Commission toured military schools, military museums, and armies in Europe, the Ottoman Empire, and the Russian Empire, where they gathered information about the war, and assessed weaponry and fortifications. After first visiting England and France, the Commission entered the Russian Empire via a train that arrived in Warsaw. They then traveled 783 miles by horse coach to St. Petersburg. For nearly two months, they toured Russian fortifications in the Baltic Sea, including the Krondstadt fortress, and visited local sites facilitated by American Ambassador Thomas Seymour.[6] The Russian government refused the Americans permission to travel directly to the front in Crimea, however, so the Delafield Commission departed for Prussia in August. When the Delafield Commission finally secured passage to Crimea from Constantinople October 8, 1855, the Russian army had surrendered Sevastopol and retreated into the peninsula’s interior. Nonetheless, the Commission spent three weeks bearing witness to the effects of modern technology in warfare.[7] Their observations and writings influenced the evolution of the American military in important ways on the eve of the American Civil War.[8] For more on the commission’s work and impact please see the works below, especially Matthew Moten’s The Delafield Commission and the American Military Profession (2000).

[1] For an English language discussion of the causes of the Crimean War, see David M. Goldfrank, The Origins of the Crimean War (New York, 1994) and the earlier John Shelton Curtiss, Russia’s Crimean War (Durham: Duke University Press, 1979), and Orlando Figes, The Crimean War (New York and London: Metropolitan Books, 2010).

[2] For a discussion of the costs of war and impacts on the Black Sea Region, see Mara Kozelsky, Crimea in War and Transformation (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2019).

[3] M. I. Bogdanovich, Vostochnaia Voina, 1853-1856, 4 vols. (St. Petersburg: tip. F. Sushchinko, 1876): 4:72

[4] American newspapers regularly published reports about the Crimean War, including material from Karl Marx who wrote for the New York Tribune as a War Correspondent, as well as reports from Richard McCormick, future governor of Arizona and speech writer for President Lincoln. See Karl Marx, The Eastern Question: A Reprint of Letters written 1853-1856 dealing with the events of the Crimean War, edited by Eleanor Marx Aveling and Edward Aveling (London: Swan Sonnenschen & Co., 1897), and Richard Cunningham McCormick, A Visit to the Camp before Sevastopol (New York: D. Appleton and Co., 1855).

[5] Matthew Moten, The Delafield Commission and the American Military Profession (College Station, TX: Texas A&M Press, 2000), 83-105.

[6] Moten, The Delafield Commission, 127-136.

[7] Moten, The Delafield Commission, 146-56.

[8] See: Richard Delafield, Report on the Art of War in Europe in 1854, 1855, and 1856 (Washington, D.C.: George W. Bowman, 1860); McClellan, George. Report of the Secretary of War Communicating the Report of Captain George B. McClellan, One of the Officers Sent to the Seat of War In Europe in 1855 and 1856 (Washington, D.C.: A. O. P. Nicholson, 1857); and Alfred Mordecai, Military Commission to Europe in 1855 and 1856, Report of Major Alfred Mordecai of the Ordnance Department (Washington, D.C.: George W. Bowman, 1860).